Self-censorship by Fear, or by Seduction?

There’s a difference between being wisely, appropriately discreet, on the one hand, and keeping inappropriately, unjustly silent, on the other. Some self-censorship is prompted by fear of speaking up because it might cost you your job and, in a repressive state, your freedom. But some self-censorship is driven by the allure of power and by a desire to get closer to power by proving that you can be trusted never to say that the emperor has no clothes.

In a talk to undergraduates at Yale in 2012, I criticized what I called a galloping culture of self-censorship that’s been woven into the lives of ambitious undergraduates at elite colleges. Such a “culture” reigns in many corporations and state bureaucracies, but a good liberal education wouldn’t train students to adapt to it. A liberal education would enable anyone to question and test conventional wisdom, not only as a student, but also, later in life, as an adult citizen of a republic and/or of the world.

The first 15 seconds of this recording are unclear, but the microphone was adjusted, and it’s very listenable after that. The talk was given outdoors, on Yale’s Beinecke Plaza.

uu007 by unknown – untitled / uu rhythm (soundcloud.com) or Stream Y Syndicate music | Listen to songs, albums, playlists for free on SoundCloud

A readable but somewhat-edited text of the talk is here on my website, but please listen to it instead at uu007 by unknown – untitled / uu rhythm (soundcloud.com).

By Jim Sleeper / September 20, 2012

The text of the talk, in 2012:

I’d like to say something today about the role that protest and remonstrance can play in restoring this depth of purpose to liberal education. And let me begin this little talk with a caveat: Not all protest or free expression advances freedom. First Amendment absolutists who push every envelope of conventional wisdom—whether in street demonstrations, in nasty Super-PAC ads, or just to play political “Gotcha” or make quick bucks—tend to forget that the people and institutions they’re pushing against aren’t wholly wrong or bad and are often more vulnerable than even the critics want them to be.

For example, those of us who’ve protested Yale’s sad slide into its dubious adventure in Singapore and into its own business-corporatization here at home are actually trying to affirm, strengthen, and even rescue something that’s vulnerable in this university and that we must be careful not to trash. Little is gained and much lost by shooting off one’s mouth and trying simply to shock the complacent into action.

But that’s not actually the argument I want to emphasize today. I want to say that discretion and caution at Yale have been carried too far, not only among administrators and faculty but even among students, who should be learning the arts and disciplines of truth-telling as well as power-wielding. That’s what you are doing in here in the Y Syndicate, but, in some other parts of this college, I notice a galloping culture of self-censorship that requires some comment.

In Singapore and in some American business corporations, self-censorship is prompted by fear of established power. That kind of self-censorship assumes many subtle modulations and guises in daily life. Even here at Yale, as I saw last spring when I attended a panel discussion called “Singapore Uncensored,” this self-censorship of fear, evident among the Singaporeans on the panel, was reinforced by some in the audience who engaged in what I’d call a self-censorship of seduction. It is prompted not by the fear of state or of corporate power but by the allure of power: Some students silence themselves almost enthusiastically, hoping to get closer to insider networking and to high status and power by proving they can be relied on never to mention that an emperor has no clothes.

Any hope for a return on this kind of self-restraint is a terrible delusion. It hastens the decay of trust and freedom inside and outside the halls of power. It has a long and quite embarrassing record at Yale, stretching back to Yalies who emerged from the college’s secret societies in the 1940s and ‘50s to perpetrate blunder after ignorant blunder in American foreign policy, from installing the Shah of Iran and stage-managing the Bay of Pigs fiasco to promoting the Vietnam War and its successors.

There’s a legitimate difference between being discreet and being silenced—between exercising a sound judgment not to do something and accepting blindly that something is simply “not done.” Agreeing to take certain things off the table can help a discussion and freedom of thought at times. But Yale today is doing little better than its old secret societies have done at teaching students when and how to draw such distinctions on behalf of a real republic, not a corporate state.

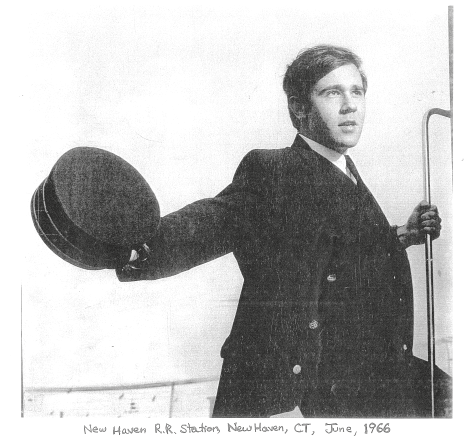

I want to tell you about some Yalies who broke courageously and constructively with both the self-censorship of fear and the self-censorship of seduction. I witnessed exactly that, right here at this war memorial, when I was 19, almost 45 years ago, and it has never left my mind.

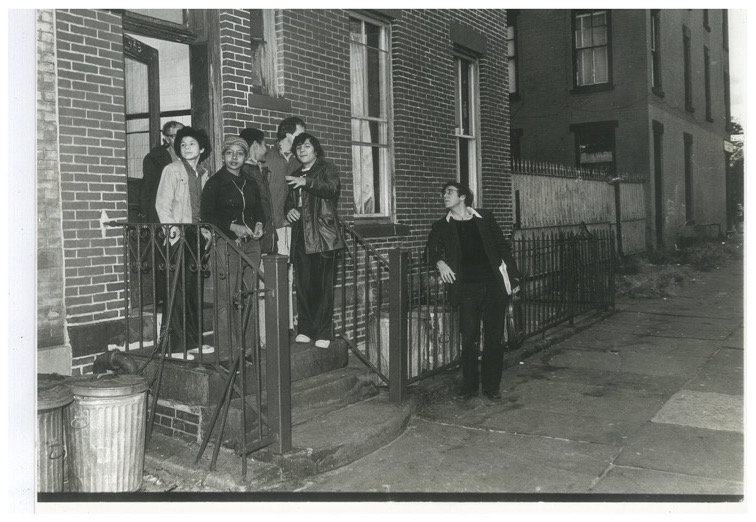

One cold, windy, wintry morning in 1968 I was plodding across this plaza on my way to a class when I noticed about fifty undergraduates gathered silently around three students and the university chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, Jr. One of the three was speaking almost inaudibly because of the gusting wind and also because he was trying to find his voice against fear. “The government claims we’re criminals,” he was saying, as I leaned in to listen. “But we say that it is the government that is criminal in waging this war.” He and the other two were about to hand Coffin their draft cards to refuse conscription into the Vietnam War upon their graduation three months later.

Coffin, speaking in the idiom of an American civil religion that too few liberals these days understand, was there to bless this demonstration of a civic courage that too few national-security conservatives understand. Near us in the Woolsey Hall rotunda were all those names young Yale graduates, graven in icy marble, under the admonition, “Courage Disdains Fame and Wins It.” The seniors before us were challenging us to join them in disdaining fame, too, but without hope of a memorial’s posthumous regard.

“Believe me,” said Coffin, himself a veteran of the CIA in Eastern Europe at the end of World War II, “I know what it’s like to wake up feeling like a sensitive grain of wheat lookin’ at a millstone.” It was a burst of Calvinist humor, a jaunty defiance of Established Power in the name of a higher one, and some of us grasped at that ray of hope, because we were scared. For all we knew, these guys were about to be arrested on the spot. Certainly if they refused induction three months later, they’d commit a felony punishable by five years in prison, and we felt arrested morally by their example because we were all carrying draft cards just like theirs in our wallets.

Yet something in these seniors’ bearing made them seem as patriotically American as Rosa Parks had been when she’d refused, only twelve years before, to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery. In both cases, the protesters broke the law openly and non-violently to evoke and elevate something noble in the very concept of law and in the whole society. Parks didn’t use freedom of speech to call the bus driver a racist mo-fo; and while the seniors did say that the government was criminal—and they would be proven right about that—by taking their stand with readiness to accept the penalty, they were also crediting the rest of us, whether we were bystanders or war supporters, with some integrity by speaking to us with clear dignity even as they exposed our shortcomings. By breaking the law in the way I’ve described, they were upholding law.

They were resisting the government in the name of a republic that stands for more than patriotic salutes to nationalist “blood and soil,” or than chants of “Yoo Es Ay!”, or even than global free-markets whose riptides are dissolving the republican virtues and sovereignty those Yale seniors were trying to redeem. The German philosopher Jurgen Habermas marveled at such demonstrations of “constitutional patriotism,” not flag-lapel patriotism.

Nathan Hale affirmed a nascent constitutional patriotism against the established but corrupted government and military of his time. And the true Tea Partiers dumped a multi-national corporation’s property into Boston Harbor to protest its collusion with a corrupt government. As I watched the seniors speaking in 1968, the old civil society of the American republic seemed to be rising from a long slumber and walking and talking again, re-moralizing the state and the law. And as Coffin intoned Dylan Thomas’ admonition, “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” my silent, wild confusion gave way to something like awe.

I tell you this not just because it happened right here, and not because anyone’s going to criminalize what we say here. I tell it because the Yale administration, which claims that it’s acting on behalf of liberal education as surely as architects of the Vietnam War claimed that they were acting for freedom and democracy, has signed a pact with, and sold its name to, a tightly controlled corporate city-state that does criminalize and otherwise intimidate people who would speak as I’m doing here.

I’m also trying to make a point about the nature of protest. Good protest requires giving clear reasons for what you are doing, even if others aren’t listening. It requires making a binding commitment to uphold what you’re affirming, not just sounding off against what you are opposing. I and other critics of the Singapore venture aren’t wishing it ill or trying to provoke an upheaval or scandal; we anticipate that the project will proceed all too smoothly. The subtle, ubiquitous and cunning self-censorship of fear that I witnessed at the “Singapore Uncensored” panel and described in the Huffington Post is meshing all too smoothly these days with the self-censorship of seduction I’ve seen growing at Yale.

The university is transforming the college from the crucible of civic-republican leadership that I saw in 1968 into a career-networking center and cultural galleria for a new global elite that doesn’t answer to any republican polity or moral code.

I’m not idealizing the past. Although Howard Dean was a freshman here in 1968 and John Kerry had graduated two years before, George W. Bush and his gang lived near me in Davenport—he was president of my roommate’s fraternity, DKE—and not everyone considered the Vietnam War a duplicitous folly. What I’m trying to show is that protest for protest’s sake accomplishes little if the protesters aren’t as serious about making clear what they’re affirming as they are about making clear what they’re exposing and opposing.

What the civil-rights movement learned from Gandhi, and what every generation must re-learn to keep a republic or a liberal-arts college, is that these institutions are fragile because they have to rely on citizens’ or students’ taking to heart and acting on certain public virtues and beliefs that neither the institutions nor markets themselves do enough to nourish or protect and that, indeed, their wealth and power may actually weaken.

Only a civic love that’s disciplined and canny enough to renew an institution’s or a republic’s higher purposes by challenging its misjudgments can accomplish anything lasting. Otherwise, as we see elsewhere, twitter revolutions and armed upheavals can intensify chaos. Only an activism that balances group organizing with the irreducibly personal conscience and courage that enabled Rosa Parks and the Yale seniors to risk their standing and security to “arrest” others morally can awaken more people to the subtle dangers to freedom. In other words, a protest strategy has to draw on wellsprings of civic faith, as Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. and even secular activists like Vaclav Havel and Adam Michnik in Eastern Europe certainly did.

When self-censorship is generated by fear of a state or a corporate employer, the fear leaves no fingerprints, as Slate political editor William Dobson put it in his new book The Dictator’s Learning Curve. In university administrations and faculties, too, there are no smoking memos that order people not to say this or that. Yet Yale’s tenurati and emeriti conduct too much of their communication only with arched eyebrows and significant silences, not with the candor and robust give and take that are the oxygen of self-government.

What troubles me even more is the culture of enthusiastic self-censorship that’s been rising among some students, driven not by fear of the state or the Yale Corporation but by the allure of becoming a powerful “inside player” after proving that one can be relied on to keep one’s mouth shut. That self-censorship is destroying the republic far more than riotous street demonstrations are. It is rendering our political and financial systems illegitimate and unsustainable. The failures of pathological, multi-problem elites in any sector you can name have become impossible to ignore.

Yet that’s precisely what too many of you are being trained to do, and it’s why there are now so many books and articles in which Yale is despised. Like fear of power, seduction by power slowly asphyxiates candor and passion in public life and generates cynicism, prurience, and hazing instead.

I’ve already mentioned the Singapore Uncensored panel, which no campus publication found the courage to report on honestly. You can read my report in the Huffington Post: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jim-sleeper/yale-has-gone-to-singapor_b_1476532.html

A few years ago, the Wall Street Journal reported that when Grand Strategy students visited West Point to discuss a book about Iraq with cadets, the Yalies “decided not to record the discussion because they did not want to have ‘views expressed in the spirit of intellectual debate be used against them at a Senate confirmation hearing’” according to Grand Strategy’s associate director, who treated this as something to brag about. Unlike the Yalies, the cadets, who’d soon put their lives on the line to defend free speech, had no fear of recording the session.

And earlier this year, when posts in The Atlantic and Foreign Policy asked why General Stanley McChrystal is teaching an off-the-record course in “leadership” in the Jackson Institute, some of his students leaped into the public arena with a statement insisting robustly that he had never asked them to sign any pledge not to disclose what’s discussed in the class. But they only wound up proving that their seminar’s supposedly broad, open discussion of “leadership” could not, in fact, be shared with anyone outside it, not even with professors teaching other courses on similar matters who invited McChrystal himself to share his insights, only to be rebuffed.

This sad misunderstanding of scholarly and democratic deliberation bears the same relation to robust freedom of speech as military music does to music. The students’ claim that freedom is fostered this way unwittingly mimicked the new Yale-National University of Singapore college’s policy of quarantining freedom to the classroom, as if it could flourish that way. Such facile misunderstandings compromised McChrystal’s own leadership on several occasions in Afghanistan before Yale hired him to teach about leadership behind closed doors.

“The sinister fact about censorship… is that it is largely voluntary,” George Orwell wrote in 1944, as his manuscript of Animal Farm was receiving rejection after rejection by frightened British publishers. “Unpopular ideas can be silenced, and inconvenient facts kept dark, without the need for any official ban…. Because of a general tacit agreement that ‘it wouldn’t do’ to mention that particular fact. It is not exactly forbidden to say this or that or the other, but it is ‘not done’ to say it… Anyone who challenges the prevailing orthodoxy finds himself silenced with surprising effectiveness….”

A true liberal education would show students how to put words on things in ways that not only expose public corruption but enlarge personal and public hope. Only by doing both can leaders lead in ways that others can trust. What I learned that wintry morning at Yale is that to kindle such trust and the courage it requires, you have to be willing to “think without banisters” at times, as Hannah Arendt put it – she meant, without a predetermined ideology — and to deepen your own and others’ love of a society or an institution by standing intelligently and affirmatively against what’s wrong in it by summoning the better angels of its nature.

_________________________________________________________

http://www.yaledailynews.com/news/2012/sep/21/levine-a-more-intellectual-yale/

A student’s comment on my talk, in the Yale Daily News:

Friday, September 21, 2012

We’ve been seduced: by a 6.8 percent acceptance rate, by the extracurricular bazaar and by the career fair. Most of all, we’ve been seduced by Tony Blair and Stanley McChrystal. We’ve been convinced, whether we ever think of ourselves in these terms or not, that we are, to use a phrase once employed to describe my high school, the “joyful elite;” that we are engaged, that we are passionate and that we are on our way to careers of real worth and standing.

We’ve been seduced — and we’ve been silenced.

Yesterday afternoon, Jim Sleeper, a lecturer in the Political Science Department, spoke to a seminar-sized group of students about what he terms “the corporatization of Yale.”

In Sleeper’s account, the University, in pursuing legitimate ends such as global engagement and fundraising, has been caught in a tide overwhelming all academia. Yale has been carried away from the values that undergird its educational mission, towards a model of opaque authority that treats students as customers.

While Sleeper’s critique focuses on the Yale administration, he contends that corporatization has also crept into the student body. Students ingratiate themselves to authority figures and take care not to jeopardize their eventual senatorial prospects. But the confusion about the purpose of the University runs deeper: Too often, we at Yale forget that we came here because we are intellectual omnivores.

We prioritize the extracurricular over the curricular. We are overwhelmed as freshmen by the number of organizations in Payne Whitney — most genuinely interesting, most of genuine value. Nothing wrong with that: Yale really is one of the few places on Earth where so many smart, motivated people are together in one place.

Yet somewhere between being swept away by the energy of our peers and the feeling of obligation to do great things with our lives, we develop unctuous habits of mind and action. We seek to distinguish ourselves within a narrow conception of professional success, prizing high grades over challenging courses, default subjects of study over those that might truly interest us and e-board meetings over office hours. These habits draw us away from the very reason Yale attracts us in the first place: academic excellence.

In short, we come to feel that what sets us apart from the rest of the world — those who didn’t get in — isn’t our intellectual prowess but what we surely will accomplish as alumni. Intrinsic motivation is crowded out by the extrinsic. Who, after all, remembers what Tony Blair studied in his Oxford days?

Hopefully, some among us will do great things in and for the world. But for many, the price of that opportunity is too dear: How many of us would say that, above all else, we are seeking out the kind of first-rate education Yale can still offer?

The Yale administration abets this. It hires with pride world leaders who bring titles with enough sheen to surpass the blemishes of their blunders on the world stage, including such gems as the Iraq War. It gestures towards educational principle by instituting distributional requirements and then abandons all pretense of rigor by offering An Issues Approach to Biology and Planets and Stars.

Even Provost Peter Salovey’s signature class, Great Big Ideas, is based on the premise that intellectual exploration is something students can’t be bothered to do outside a class.

Perhaps worst of all, the Admissions Office fails to emphasize — the way, say, the University of Chicago or Swarthmore does — that one comes to Yale to learn.

It’s easy to treat education solely as a path to gainful employment, especially when that’s so hard to find. But Yale can provide haven from those practical pressures. These are the only four years in our lives when we can devote ourselves to thinking.

As the University selects its 23rd president, we students must do everything in our power to ensure that the first priority of those who lead our institution is to rejuvenate its intellectual climate. Of course, President Levin, over the last two decades, has been invaluable in ensuring that the facilities and faculty are of the highest caliber. But those efforts will have been wasted on Yale College if we take no joy in the life of the mind. Now, from the bottom of this University, we must reclaim our highest intellectual ideals and demand that those at the top do the same.

Gabriel Levine is a junior in Trumbull College.