Fareed Zakaria’s Problem — And Ours (8/18/11)

Fareed Zakaria’s Problem – And Ours

By Jim Sleeper – August 18, 2011, 8:42PM

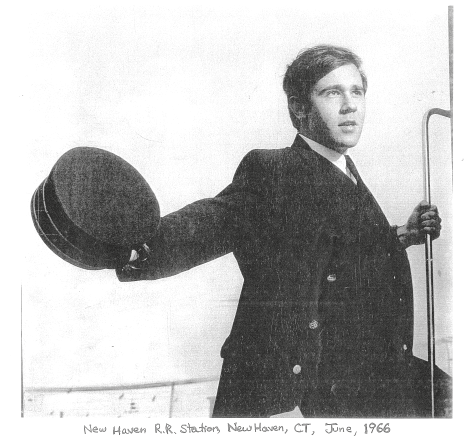

Many people defer to Fareed Zakaria’s virtuosity and sheer ubiquity as the neo-liberal consciousness-shaper of the moment. An Indian Muslim by background whose parents have been prominent in Indian politics and news media, he owes a lot of his credibility as a journalist to American civic-republican premises and a generosity of spirit that had some force in undergraduate life at Yale when Zakaria was a student there. (He graduated in 1986, then earned a PhD from Harvard). But now that America’s civic-republican premises and practices are waning, Zakaria’s own recent behavior makes me wonder how well they ever “took” with him in the first place.

At age 28, he was managing editor of Foreign Affairs; later, as editor of Newsweek International, he began hosting his Emmy Award-winning CNN program “GPS,” where he holds forth now while writing for Time magazine. Certainly, he has given America a lot, though often by dishing out more “wisdom” than he takes in return as he weans us of what he considers our democratic naivete.

Steely in command of his facts and allusions, he’s as deft as he is disciplined: Asked to assess the Iraq War this year at an inaugural convocation of Yale’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs (home now of Stanley McChrystal), he said that while “it’s clear now that costs outweighed benefits and that anyone who says he’d do it over again is not being honest or is not in command of the facts,” we must remember that South Korea, too, seemed “a big mess, a brutal dictatorship, until the 1980s,” when it stabilized and became hospitable to Western values as well as investments. All the same, he added, we should try to “re-balance American foreign policy away from these crisis centers that are riven by 15th-century feuds.”

That strikes me as an example of how Zakaria manages to eat his cake and keep it, too, when parsing the movements of the powerful if myopic titans whose policies he so often and so smoothly defends. So it was something of a surprise to see him lose his cool and his command of the human prospect last week, on the Charlie Rose show, in an id-like eruption over the political psychologist Drew Westen’s darkly prophetic, potentially game-changing New York Times essay, “What Happened to Obama?”

Like the 13th chime of a clock, Zakaria’s arrogant outburst not only surprised; it cast doubt on the previous 12 chimes of the centrist, high-Democratic bloggery and flummery that he sometimes superintends as concert master of our national orchestra of high-minded liberal opinion.

Understand first what’s at stake in all this. During the 2008 campaign, Barack Obama – a kindred spirit of sorts to Zakaria (though not an immigrant or a Muslim like him, rumors to the contrary notwithstanding) — was photographed boarding a plane holding Zakaria’s best-selling The Post American World. That book had followed another best-seller, The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad, and both have been translated into 20 languages.

CNN’s “GPS” stands for “Global Public Square,” but Zakaria is a Global Positioning System by himself, a one-man Davos for the casino-finance, corporate-welfare, consumer-bamboozling wrecking ball whose directors, grand strategists, investors, and apologists brandish pennants of their “diversity” as talismans against having to answer to any actual polity or moral code, national or otherwise.

He sits on the governing corporation of Yale University, a career-networking center and cultural galleria for the new global elite so memorably (and scathingly) depicted by Chrystie Freeland in The Atlantic. (Yale is just now establishing a whole new liberal-arts college in Singapore, a city-state that, as Maureen Dowd noted, thinks and acts more like a global corporation than a republic.)

Although Zakaria is also a board member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Trilateral Commission, he considers himself enough a Democrat — and democrat — to tell the masses, via CNN and Time, why the neo-liberal dispensation of Obama, Bernanke, Geithner, et al is inexorable and inescapable and why, with public acquiescence to the judgments of such experts, it’ll probably be all for the best, or at least better than any alternative.

He assesses that dispensation’s costs, benefits, and (limited) opportunities for democratic mitigations in the style of a grand-strategic memo-writer, his rat-a-tat-tat diction issuing in firm, clear judgments graced with felicitous apercus. If he rests, it’s because he’s disarmed all intellectual and moral resistance, at least for the moment.

The New Republic’s American-politics blogger extraordinaire, Jonathan Chait, teamed up with Zakaria on the Charlie Rose show in a show of force against Westen, who is himself the author of a best-seller, The Political Brain. Zakaria and Chait deferred to and praised each another more often than they actually addressed Westen, whom they dismissed as an ivory-tower moralist with no political experience. They dispensed Beltway realism about the filibusters and the fiscal-crisis constraints that supposedly moot Westen’s demand for a President who’ll tell Americans more of the truth about the crisis they face, in an empowering, explanatory, narrative in the manner of FDR, Martin Luther King, Jr., or even Harry Truman.

Rose opened the show with a clip that showed Obama falling well short of the standard that Westen invokes, the President blaming Congress and not the larger powers to whose tunes it dances. “This downgrade you`ve been reading about could have been entirely avoided if there had been a willingness to compromise in Congress,” Obama said. “See, it didn`t happen because we don`t have the capacity to pay our bills. It happened because Washington doesn`t have the capacity to come together and get things done. It was a self-inflicted wound. There is nothing wrong with our country. There is something wrong with our politics.”

Westen counters that Obama’s account isn’t enough of the truth to be even credible: There’s “something wrong” not just with our politics but with that global juggerrnaut that’s distorting and, indeed, dissolving it.

For example, manufacturers that have outsourced their jobs and/or closed their plants were doing fine with, say, a 15% rate of profit before their new, publicly traded conglomerate owners demanded, say, a 22% rate of return. By what God given or natural right? By no right besides a long train of decisions by the corporate bought-and-paid for Congress or the courts and by global market pressures that no polity is permitted to challenge.

That Obama won’t say this clearly is a point of Westen’s essay. Drawing not just on his knowledge as an academic psychologist — as his critics suggest disparagingly — but also from history, anthropology, and his own substantial experience as a Washington political consultant, Westen writes that:

“The stories our leaders tell us matter… because they orient us to what is, what could be, and what should be…

“When Barak Obama rose to the lectern on Inauguration Day, the nation was in tatters…. Americans needed their president to tell them a story that made sense of what they had just been through, what caused it, and how it was going to end….”

Westen tells the story he thinks Obama should have told: “This was a disaster, but it was not a natural disaster. It was made by Wall Street gamblers who speculated with your lives and futures. It was made by conservative extremists who told us that if we just eliminated regulations and rewarded greed and recklessness, it would all work out…..”

He sketches the parameters for a solution that Obama should have proposed: “We will restore business confidence the old-fashioned way: by putting money back into the pockets of working Americans by putting them back to work, and by restoring integrity to our financial markets…”

Such a story, he claims, would have “inoculated against much of what was to come in the intervening two-and-a-half years of failed government, idled factories, and idled hands. [It] would have made clear that the president understood that the American people had given Democrats the presidency and majorities on both houses of Congress to fix the mess the Republicans and Wall Street had made of the country…. It would have made clear that the problem wasn’t tax-and-spend liberalism and the deficit – a deficit that didn’t exist until George W. Bush gave nearly $2 trillion in tax breaks largely to the wealthiest Americans and squandered $1 trillion in two wars.

“And perhaps most important, it would have offered a clear, compelling alternative to the dominant narrative,… that our problem is not due to spending on things like the pensions of firefighters but to the fact that those who can afford to buy influence are rewriting the rules so they can cut themselves progressively larger slices of the American pie while paying less of their fair share for it.

“But there was no story, and there has been none since,” Westen writes.

This was all too much for Jonathan Chait, who told Rose that Westen’s is “a dramatic overestimation of the power of rhetoric to affect policies in Congress and to affect public opinion. There`s just not a lot of evidence that it has that kind of effect, anything like the effect that — that he says.

“I think liberals have a hard time holding on to power and being comfortable with power and the compromise is held with power,” Chait continued. “I think it`s something in the liberal psyche…. I am not the psychologist here, but liberals turn against every single Democratic President with regularity. That was what the whole Nader campaign in 2000 was about, this fury that Clinton was a sell out.

“Now we`ve had a President who`s been vastly more successful in advancing the liberal agenda through Congress and you`ve got liberals angry again…. But the anger at Obama to me is just sort of baffling.”

Zakaria, no slouch at reductio ad absurdum in combat with liberals — and a near-screecher whenever he has to talk about leftists — outdid Chait, even while siding with him:

“Jonathan is entirely right but he doesn`t go far enough for my purposes. As Jonathan says in a very brilliant blog post, [Westen’s] is the version of the American presidency you get from Aaron Sorkin in [the movie] “The American President”: The President gets up, and makes this incredibly moving speech which is, of course, deeply liberal. The entire country cheers and all of a sudden all the problems that are — that he encounters are waved aside.

“You remember, in the movie, of course, it was gun control and environmentalism that was the big problem. Now, the idea that if Barack Obama were to give a speech on gun control, suddenly he would be able to, you know, wave aside the Second Amendment and the — settled convictions of a large percentage of Americans is — is we would recognize nonsense.

“The reality is that Obama is working within a very constrained political environment,” Zakaria continued, citing Obama’s accomplishments against great odds; “I`m a little hard pressed to see what the great liberal betrayal has been other than from some kind of fantasy version of liberalism where the American — you know, finally a Democratic president comes in and America becomes, I don`t know, Sweden.”

Little of this had anything to do with Westen’s argument, and as the discussion got down to political specifics, Chait and Zakaria went on about the filibuster and the self-interest of members of Congress, blaming them and the American people, not the President.

Finally, Rose asked, “….Yes, [Obama] had a difficult Congress to deal with, but if he had a different set of skills and was less of a conciliator, might he achieved more? That`s the question that Drew raises.”

Chait: “I don`t think that`s right. He only had four months in which he had 60 votes in the Senate. Other than that period, Republicans were committed to blocking his entire legislation no matter what, pretty much even if it included ideas that they had once endorsed. The President just has very limited tools at his disposal….

Rose: Drew?

Westen: “Well, I will say that I have more empathy for the President now after feeling like what it`s like to have a filibuster proof super-majority of two against one.”

Then Westen disposed of the filibuster argument: “President [George W.] Bush never had the size of the Senate behind him that President Obama had when he walked into office and that he then had three months later.

“And President Bush ….got through ‘No Child Left Behind,’… tax cuts …. heavily weighted towards the wealthy. He got through an unfunded Medicare plan that gave lots of money to Big Pharma. He got through an unfunded Iraq war, an unfunded Afghanistan war. And where was the screaming about the deficit then? Where was the screaming about the filibuster?

“By January of 2009, when [Democrats] could have changed the rules in the Senate, [they] chose not to…. They knew who they were dealing with. Obama certainly knew who he was dealing with after the first couple of times of banging his head against the wall and realizing, wait a minute, these are not Rockefeller Republicans. So why didn`t they change those rules? Why didn`t he push them to change those rules?”

Zakaria changed the subject, going back to blaming the people. “Look, the American people… they want jobs. They want the budget deficit cut. They, by and large, don`t want much taxes, many new taxes other than on the very rich. They don`t want Medicare cut, they want Social Security preserved, they don`t want the interest deduction on mortgages to be taken away but they want many large cuts. You know, this is a conglomeration of incompatible desires.

“And, to Drew`s point again, why is Obama worried about this? …. We have a budget deficit that is 10 percent of GDP. It`s the second-highest in the industrialized world. We have a gross national debt that will approach 100 percent in three or four years. So, you know, we`re not in the 1930s when — when government debt was minuscule in comparison. We can`t just say let`s spend $5 trillion jump starting the economy and see where that gets us.

“[This] does not show that Obama has been captured by bankers, He is properly concerned that there is some outer limit about how much you can spend and therefore a long-term deficit reduction plan is the right thing….. : I think sometimes being a conciliator is being a leader, particularly in a divided country.”

Westen: “Do you really think, though, that what we need right now, when we`ve got a Tea Party dominating the House, is someone who`s trying to conciliate people who you`ve just said a minute ago can`t be conciliated?”

Zakaria: “Drew, Drew, the stimulus package, such as it was, passed by one vote. The idea that if you had added on another $400 billion it would have sailed through, I mean this is what he could get through…..”

Westen: “Well, I actually was asked by the leadership of the Senate to help out… with Wall Street reform. And one of the things that [we] said was, “Look, do what the Republicans did to you: call votes. If you`ve got 59, call a vote, and … you say, look, we`ve got us voting for Main Street, we`ve got them voting for Wall Street.”

“Harry Reid did that, I think, three days in a row and the 60th vote was there [because some Republicans, frightened by the public criticism, defected.] That was what could have been done… with the stimulus, but was not done.

“And in fact, at that point the President had 80 percent popularity of the American people… He had 57 sure votes in the Senate,… an overwhelming majority in the House. ….I never thought I`d ever say anything good about George W. Bush — but you do what George Bush did,… you go over the heads of members of Congress….

“And you say to [the moderate Maine Republicans] Susan Collins and…. Olympia Snowe, ‘Listen, the story is that 750,000 people a month are losing their jobs right now. I want to show you… a picture of a little girl who just lost the room in her house that was taken away from her. If you`re going to vote against this stimulus package, I`m going to make sure that when we get 58 votes or 59 votes tomorrow, the American people are going to hear about why it is that they`re still losing 750,000 jobs a month.’

“And I`ll bet you it would have taken three votes that he would have gotten the stimulus package he wanted.”

It was at this point that Zakaria, seeing that he wasn’t going to crush what he’d thought was an ivory tower moralist, lost his composure. “Look I — what I would say, and I`m not going to get into the what-ifs of a professor, you know, who has never run for dogcatcher advising one of the most skilful politicians in the country on how he should have handled this. It`s a – “

Rose intervened, saving Zakaria from himself: “The former would be you and the latter would be President Obama? “

Zakaria, deft on the uptake, trying to right himself, said, “Yes, exactly. The whole idea that all of us who`ve never run for anything have you know, have — can brilliantly explain how to maneuver another $400 billion through the Senate. You know, maybe. Maybe.

“But I will say. maybe we would all agree [that] it isn`t clear what you can do. You are facing a very serious economic crisis….. a very deep jobs crisis…. It`s happening because of globalization: It`s happening because of technological change that is causing companies to be much more productive. It`s happening because of a degradation of educational skills of the American work force. It`s happening because of this huge de-leveraging that`s taking place which is making all businesses less risk-seeking…..

“So I`m also a little uncomfortable with people who have facile answers if only he would have waved his magic wand. “

Oops, again.

Rose, again: “I don`t think anybody`s arguing that there`s a magic speech to be made. I do think people can make a legitimate question, which is, Did this president exhibit the kind of skills that he may or may not have that would have produced a different result at various stages in his presidency? These have to do with leadership skills….”

* * *

A day after the show, Zakaria scrambled to cover his gaffe in two blog postings that tried to slam the lid down on it. At 6:35 am on the Saturday after the Thursday night show, he posted on his CNN blog, under the headline, “What Liberals Fantasize About”:

“Thursday night I was on Charlie Rose talking with Drew Westen, a professor of psychology at Emory University and Jonathan Chait, a senior editor with The New Republic.

“Drew wrote a provocative article in the New York Times called ‘What Happened to Obama?’ It’s a scathing critique of President Obama’s leadership. Then, in a brilliant blog post, Jonathan Chait called Drew’s argument a fantasy…

“Here’s a lightly edited excerpt of our conversation where I discuss the fantasy of liberals and why many need to grow up.”

But Zakaria edited his transcript of the show heavily, dishonestly. His excerpt is 1588 words long; the actual Rose transcript of the same portion of the show is 5700 words. Zakaria’s version obliterates Westen’s arguments about the missed opportunities in Congress and other political specifics, along with Zakaria’s own condescending response to the professor who’d never run for dog-catcher. In the last half of Zakaria’s version, he and Chait end up talking to each other as if Westen weren’t right there on the show. “Visit CharlieRose.com for the full video,” Zakaria advises piously in a note at the end of his post, knowing that few who’ve read his version will bother.

In another blog post, this one for Time, Zakaria frets that “The air is thick with liberal disappointment. In the days after the debt deal, liberal politicians and commentators took to the airwaves and op-ed pages to mourn the agreement. But their ire was directed not at the Tea Party or even the Republicans but rather at Barack Obama, who they concluded had failed as a President because of his persistent tendency to compromise.

“As the New Republic’s Jonathan Chait brilliantly points out, this criticism stems from a liberal fantasy that if only the President would give a stirring speech, he would sweep the country along with the sheer power of his poetry. In this view, writes Chait, ‘every known impediment to the legislative process–special interest lobbying, the filibuster, macroeconomic conditions, not to mention certain settled beliefs of public opinion–are but tiny stick huts trembling in the face of the atomic bomb of the presidential speech.'”

Again, Zakaria compounds Chait’s own reductio ad absurdum and contempt for what Westen has actually argued: “The disappointment over the debt deal is just the latest episode of liberal bewilderment about Obama,” Zakaria writes, characterizing Westen as “confused over Obama’s tendency to take ‘balanced’ positions”. Zakaria argues, falsely, that Westen suggests “that his professional experience– he is a psychologist –suggests deep, traumatic causes for Obama’s disease. Let me offer a simpler explanation. Obama is a centrist and a pragmatist who understands that in a country divided over core issues, you cannot make the best the enemy of the good.”

Zakaria then intones that “while banks need better regulations, America also needs a vibrant banking system, and that in a globalized economy, constraining American banks will only ensure that the world’s largest global financial institutions will be British, German, Swiss and Chinese.” He writes that Obama understands “that Larry Summers and Tim Geithner are smart people who, in long careers in public service, got some things wrong but also got many things right.”

This seems to have been written by someone a bit too defensive and full of himself to respect his readers’ intelligence. Sure enough, Zakaria pulls out the elite card:

“Obama’s temperament was eloquently expressed by the late Bart Giamatti, a former president of Yale and former baseball commissioner, when he urged students not to fall prey to ideology from the right or left… ‘My middle view is the view of the centrist,’ he said, before quoting law professor Alexander Bickel, ‘who would … fix “our eyes on that middle distance, where values are provisionally held, are tested, and evolve within the legal order derived … from the morality of consent.'” To set one’s course by such a centrist view is to leave oneself open to the charges, hurled by the completely faithful of some extreme, of being relativistic, opportunistically flexible, secular, passive, passionless … Be of good cheer … To act according to an open and principled pragmatism, to believe in the power of process, is in fact to work for the good.'”

Ah, well. I understand the temptation to wax a bit nostalgic about the wisdom of the Yale president of one’s undergraduate years, as Zakaria has done here. I’ve sometimes done that myself in praising Kingman Brewster, Jr., a descendant of the minister on The Mayflower, who gave a Yale honorary doctorate to Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1964, when that was a very controversial, not centrist, thing to do. (Giamatti got his own real doctorate the same day).

If it’s enlightened “centrism” we’re looking for, Brewster bucked more than a little alumni resistance when his gesture helped to draw King into the center of his time, a center that otherwise might not have held. Now that our own center is imploding, what would Zakaria do about it?

He and other apologists for the Democratic Party’s neo-liberal paradigm probably haven’t expected to end up looking like the “old Blues” who protested Brewster’s honoring King. But they’re beginning to sound like charter subscribers to the Beltway dog and pony show’s crackpot “realism,” its feints toward an American pragmatism that has succumbed to the casino-finance, corporate-welfare, consumer-defrauding premises it no longer questions.

Some dimensions of philosophical pragmatism may actually weaken or distort civic-republican affirmations like Westen’s and, with them, real movements for social justice. What, for example, is pragmatism’s defense against those like Zakaria who confuse the hubbub of free-markets with democratic deliberation and celebrate global capitalism itself as pragmatic, anti-absolutist, inherently democratic, and historically liberating?

The American historians Christopher Lasch and Jackson Lears have warned that the wealthy and powerful sometimes cling not to the old racist, nationalist, or religious nostrums that most people associate with power but to swift market currents that assume the benign mantle of pragmatism even as they destroy the communities and values on which many people depend.

What Zakaria hails as “centrism” becomes, in his hands, little more than an excuse for elites who are wreaking such destruction and are seeking desperately to rationalize it. (No one lamented this more, by the way, than Zakaria’s hero Giamatti, who described a university president’s life as that of a fund-raising song-and-dance man).

Sometimes, adopting such rationalizations does involve telling national governing elites certain hard, “pragmatic” truths that do have to be reckoned with. At Yale’s Jackson Institute, Zakaria told his audience that “A billion people now do jobs that American middle class and workers, blue and white collar, used to do.” And he doubted that either political party could do much about it. Once, Americans had all the capital and the know-how, he said, but, now, other peoples “have the resources, and they know how.”

The audience was silent in gloomy acquiescence, but why? Zakaria’s interlocutor on stage, Yale President Richard Levin, an economist, opined that a bigger stimulus might have a more redemptive multiplier effect on the economy than Zakaria allowed, and that is only the beginning of what ought to have been said. Neither man questioned the rules of the game under which corporations have evolved, not only on their own initiative but through decades of jurisprudence that amounts to an extended lie the United States has been telling itself about the nature of its economy and of itself a republic.

That’s a story for another time; suffice it to say here that an alternative narrative — even a “centrist” one that Giamatti and Brewster might have endorsed — would ask whether and now the rules of global capitalism need to be rewritten.

In other times and places, people with the integrity required for such a challenge led unarmed, seemingly powerless, yet deeply sensible and well-organized movements that, against all expert and elite expectations, brought down vast-national security states anchored in injustice — apartheid South Africa; the segregationist regime of the American South that even Clarence Thomas called “totalitarian;” the Soviet empire in Eastern Europe with a minimum of armed conflict: “How many divisions has the Pope?” Stalin once quipped. When Pope John Paul II stepped off a plane in Warsaw, greeted by a million unarmed Poles, Stalin’s successors got their answer. The best explanation of this kind of power is in Jonathan Schell’s The Unconquerable World. I commend it to Zakaria and Chait for a long, slow reading.

One of the places it worked was, of course, British India, two decades before Zakaria’s birth. But is there a nerve or bone in his body that responds sympathetically to such movements?

“When Dr. King spoke of the great arc bending toward justice,” Westen writes, “he did not mean that we should wait for it to bend….. He… knew that whether a bully hid behind a [policeman’s billy]club or a poll tax, the only effective response was to face the bully down, and to make the bully show his true and repugnant face in public.”

As Zakaria spoke darkly about the professor who’d never run for dog-catcher and who thought he could wave a magic wand, I thought I saw the face of a bully’s consigliere. Our one-man Davos, usually so camera-ready and composed, morphed into something almost cadaverous, a caricature of a bewigged Tory chiding Levelers. He did it again on his own CNN program, telling “liberals” to “grow up.”

What Westen wants is — in his own words, in the Times essay that deserves re-reading at the end of this discussion — is “a clear, compelling alternative to the dominant narrative,” one that explains “that our problem is not due to spending on things like the pensions of firefighters but to the fact that those who can afford to buy influence are rewriting the rules so that they can cut themselves progressively larger slices of the American pie while paying less of their fair share for it.”

It would be heartening to see Zakaria, Chait, and other writers — who have more freedom than presidents, yet who seem driven to defend the corporate state and the Democratic Party in their present forms — form their own mouths around the following words:

The global casino-finance, corporate-welfare, consumer-bamboozling juggernaut may feel inexorable and inescapable to most of us. But for that very reason it is becoming illegitimate and is unsustainable. Our responsibility as writers is to help to develop public narratives that pose the right questions and possibilities.

Westen’s courageous essay is especially

gratifying to me because, when he was a freshman in a Harvard expository writing class I taught in 1976, he recounted a story, worthy of the movie “The Insider,” about his own father’s brave but suppressed efforts to get the tobacco company where he worked as a research scientist to come clean about the health risks of its products. I can’t help wondering if Zakaria would have overlooked or minimized those risks had he been around at the time when Westen’s Dad was trying to air them.

Obama himself has written of his debt to “the prophets, the agitators,… the absolutists…. I can’t summarily dismiss those possessed of a similar certainty today.” Why can’t Zakaria and Chait write that, too, especially when the “agitator” is as reasonable and sophisticated as Drew Westen? What drives them to portray him as some kind of naif or crank? Was it the long list of talking-points rebutting Westen that the White House reportedly issued the morning his essay appeared?

The pundits have circled their wagons, but “Thought is not, like physical strength, dependent on the number of its agents,” Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America. “On the contrary, the authority of a principle is often increased by the small number of men by whom it is expressed. The words of one strong-minded man, addressed to the passions of a listening assembly, have more power than the vociferations of a thousand orators….. Thought is an invisible and subtle power, that mocks all the efforts of tyranny.”

And of tyranny’s deniers and obfuscators, too.

Dear Fareed, Jonathan, Barack: What seems inexorable and inescapable to you ma seem illegitimate and unsustainable to millions before long. The more that reasonable truth-tellers like Drew Westen take their stand against it now, the fewer cranks, agitators, and absolutists you’ll have to contend with later.

I really suggest re-reading Westen and, instead of nit-picking and deriding, connecting with the arc of justice as other unlikely but transformative movements in history have done.

_____________________________________________________

From The New Republic’s list of 'overrated thinkers':

http://www.tnr.com/article/politics/96141/over-rated-thinkers?page=0,1

FAREED ZAKARIA

Fareed Zakaria is enormously important to an understanding of many

things, because he provides a one-stop example of conventional

thinking about them all. He is a barometer in a good suit, a creature

of establishment consensus, an exemplary spokesman for the

always-evolving middle. He was for the Iraq war when almost everybody

was for it, criticized it when almost everybody criticized it, and now

is an active member of the ubiquitous “declining American power”

chorus. When Obama wanted to trust the Iranians, Zakaria agreed (“They

May Not Want the Bomb,” was a story he did for Newsweek); and, when

Obama learned different, Zakaria thought differently. There’s

something suspicious about a thinker always so perfectly in tune with

the moment. Most of Zakaria’s appeal is owed to the A-list aura that

he likes to give off—“At the influential TED conference ...” began a

recent piece in The New York Times. On his CNN show, he ingratiates

himself to his high-powered guests. This mix of elitism and banality

is unattractive. And so is this: “My friends all say I’m going to be

Secretary of State,” Zakaria told New York magazine in 2003. “But I

don’t see how that would be much different from the job I have now.”

Zakaria later denied making those remarks.